Four minutes in the Circle

A visit to the Grand Ole Opry concludes on a high note

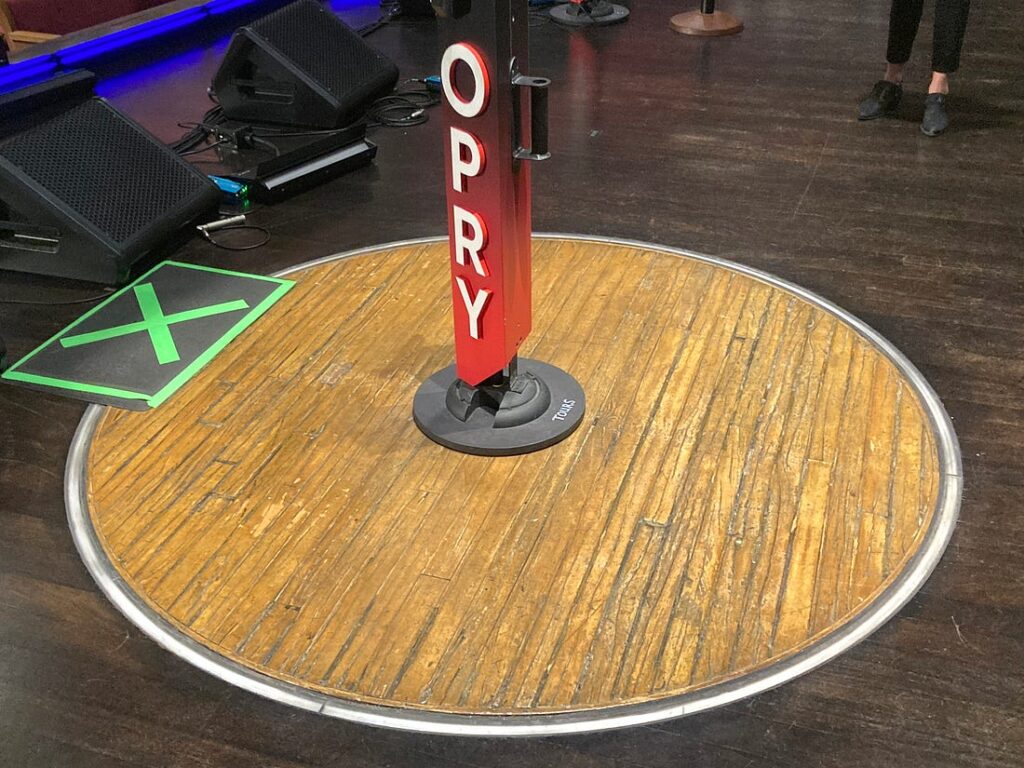

- “The Circle” at center stage of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee, pictured Friday, April 11, 2025, was brought over from the Opry’s previous home at Ryman Auditorium. PHOTO BY AUTHOR

- The Grand Ole Opry House is pictured in Nashville, Tennessee, Friday, April 11, 2025. The Opry debuted on November 28, 1925, as the “WSM Barn Dance” and WSM-AM now broadcasts from a building just to the left. PHOTO BY AUTHOR

The Grand Ole Opry House is pictured in Nashville, Tennessee, Friday, April 11, 2025. The Opry debuted on November 28, 1925, as the “WSM Barn Dance” and WSM-AM now broadcasts from a building just to the left. PHOTO BY AUTHOR

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – I had hours remaining before my return flight, and timed tickets were going to be the end of me.

I had lucked out with a slot at the Hermitage, the estate of former president Andrew Jackson, that got me in the door right as a downburst of rain stalled over the place for half an hour. By doing that first, though, I couldn’t commit to the next stop, and when I showed up, there were only two tour times left. “I’ll take the 3:45,” I said, which meant an 80-minute wait for a nearly $50 tour of the Grand Ole Opry.

The tour started in a small room with a projected video of Garth Brooks and Trisha Yearwood sharing the history of the Opry. It showed us Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville, where a radio variety program called the “WSM Barn Dance” first aired Nov. 28, 1925. That show, which was renamed the “Grand Ole Opry,” celebrated its centennial throughout 2025.

The current Opry building on the outskirts of Nashville dates to 1974, but a circle of flooring from backstage at the Ryman was carved out and brought to center stage here. This symbolic move connects with the old song “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?”, which has multiple versions and dozens of covers from the Carter Family to the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Performing in the Circle, physically and symbolically standing where so many others have before, is a country music singer’s dream.

As the presentation ended, the tour guide said everyone would have a chance to stand in the Circle. “And if you’re interested,” she said, “start thinking about what you want to sing.” Oh?

“The Circle” at center stage of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee, pictured Friday, April 11, 2025, was brought over from the Opry’s previous home at Ryman Auditorium. PHOTO BY AUTHOR

Guys do it all the time

Opry members have their own mailboxes, and some even come in and pick up their own fan mail. We saw the dressing rooms, each with their own theme, renovated after a 2010 flood ruined everything inside (the Circle was saved). There’s a comedy room named after Minnie Pearl. There’s a patriotic/veterans room. There’s a room celebrating the women of country music, a topic that deserves some reflection.

The country music business, sadly and notoriously, has been rough ground for women. For every Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, or Dolly Parton there were more who tried for years to get a shot but didn’t make it big. That began to change in the 1980s as Tanya Tucker, the Judds, and Reba McEntire paved the way for more women in the 1990s. For a microsecond, Nashville was ready to dare fans to buy an album called “Did I Shave My Legs For This?”

Men of the “hat era” of country, starting with Brooks’ self-titled album in 1989, got much of the attention, but they line-danced with an equally talented and assertive collection of women. Mary Chapin Carpenter’s “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her,” about a woman unfulfilled with her life as an unappreciated wife — and a takedown of a 1970s TV ad — was the most feminist country song on mainstream airwaves until Shania Twain’s “Man! I Feel Like a Woman” (self-explanatory). That was the most girl-power song on mainstream airwaves until Miranda Lambert’s “Gunpowder and Lead,” with a protagonist who’s ready if her abusive ex comes looking for her.

Turn on the radio

For about 15 years, women could be found up and down the country music charts. Kathy Mattea. Martina McBride. Jo Dee Messina. Terri Clark. Patty Loveless. Pam Tillis. Faith Hill. Mindy McCready. Sara Evans. McEntire and Yearwood.

Despite country music’s unprecedented growth in this period, it swam alongside the pop culture stream, but not in it. New York City did not have a country music station between 1996 and 2013, and hasn’t had one since 2021. San Francisco lost its last one in 2022. Los Angeles hasn’t had a country station since 2006. If you don’t exist in those cities, pop culture has one word for you: niche.

In terms of airplay frequency, women were soaring at the end of the 20th century. Of the 19 songs in 1999 to hit #1 on Billboard Hot Country, eight were sung by women (McBride twice) and another was a duo of Clint Black and his wife, Lisa Hartman Black. Then the decline hit. Five years later, in 2004, of 15 #1 songs, four were sung by women and only one (Gretchen Wilson’s “Redneck Woman”) lasted more than a week at the top.

The brightest spots of the 2000s came from reality television, which gave us Carrie Underwood in addition to Lambert, and from one out-of-nowhere teenager who convinced her parents to move to Nashville so she could sing a song about a ’90s country star. Underwood, Lambert, and Taylor Swift helped pull country music along until 2012, when four words — “BABY YOU A SONG”— threw the genre back into the caveman days.

There’s your trouble

“Bro-Country is a plague, and Florida Georgia Line is Patient Zero,” read one of the best headlines ever written about country music, in the Broward-Palm Beach New Times in 2015. “Their debut single, ‘Cruise,’ is the best-selling country digital song of all time. And yet the band is among the most insufferable acts to ever muck up the stage.”

FGL was a pioneer in the bro-country subgenre, where the songs revolve around drinking, trucks, girls, and drinking in trucks with girls. Nothing could stop it. A couple of Underwood albums and Tim McGraw’s “Southern Voice,” all full of well-crafted lyrics that had a story, if not also a message, stood no match for lines like “Trucks jacked up, flat bills flipped back / Yeah, you can find us where the party’s at.”

Country music historically has had a complicated relationship with alcohol, but it hit new lows during the late Obama/first Trump era. Radio was no longer a place for something sweet like Tucker’s “Two Sparrows in a Hurricane” from 20 years earlier. It got to the point where there was an attempt to split ’80s/’90s country from more recent stuff as a format, but the idea didn’t get much traction.

Women had hit a high-water mark of 52% of the No. 1 country songs of 1998and 34% of total country radio airplay in 1999. A decade and a half after that, Tomatogate struck.

“[Keith] Hill cautions against playing too many females, and playing them back-to-back, he says, is a no-no,” Country Aircheck Weekly reported May 26, 2015, in an interview with a music scheduler.

“‘If you want to make ratings in Country radio, take females out,’ he asserts. ‘The reason is mainstream country radio generates more quarter hours from female listeners at the rate of 70 to 75%, and women like male artists. … The lettuce is Luke Bryan and Blake Shelton, Keith Urban and artists like that. The tomatoes of our salad are the females.'”

In 2019, although radio was no longer core to music success, female country singers had fallen to 10% of daily “spins.” The bro-country era might have wound down/backed off since then, but it’s still very difficult for women to break in to mainstream country without soon splitting off to pop, folk, or Americana. Kelsea Ballerini is a recent exception. Lainey Wilson is another.

Male singer Morgan Wallen, meanwhile, was caught on video in 2021 saying the N-word while drunk. His punishment was one year out of the spotlight, followed by 26 non-consecutive weeks at #1 in 2023 on the Billboard Hot Country chart, plus 28 consecutive weeks at #1 (and a one-off) in 2025, either by himself or with a co-singer.

This one’s for the girls

Back at the Opry, the tour guide walked us through the backstage area and then to center stage, where instruments had already been set up for the night’s performance. At front and center was a circle of old hardwood and one microphone with the word “OPRY” posted on the stand. An off-the-record taste of country music’s promised land beckoned.

To select my song, YouTube was out — too time-consuming to look, I might grab the wrong version, and I could be interrupted by an ad or buffering. That limited me to the small collection I had on my iPhone. A fast-paced, upbeat song wouldn’t feel right in the empty auditorium, and besides, I don’t have Underwood’s pipes.

It had been precisely 25 years and one month since the last time I sang solo on a stage in front of an audience. “Audience” here is a generous term, as this one was comprised of the other tour members, the guide, a few random employees in the balcony/sound booth, and an official photographer who probably endures dozens of wannabes every day on the off chance a few will pay $30 for the photo. The microphone was a prop. The rows were empty. But I was here, in the Circle, at the Opry, and no one else wanted to sing.

With the options I had, I reasoned that it was only fitting to do a tiny tribute to the women of country music who contributed to the soundtrack of my life.

I pushed my phone’s volume up to max, made Lambert my backup singer, and did my best to soak up the moment while also hoping to hit 90% of the words. I was going to sing until the tour guide stopped me. She didn’t.

When I finished “The House That Built Me,” I let the last guitar strands play out and sighed. Yes, anyone who takes the tour has this opportunity. No, I didn’t sing perfectly, I didn’t get any applause, and it wasn’t broadcast. But, technically, I sang a complete song while standing in the Circle of the Grand Ole Opry.

To quote a Yearwood song I wore out in high school, the song remembers when.

References

“Guys Do It All The Time,” Mindy McCready, 1996; “Turn on the Radio,” Reba McEntire, 2010; “There’s Your Trouble,” Dixie Chicks, 1998; “This One’s For the Girls,” Martina McBride, 2003

Jeff Morrison is the writer behind the website “Iowa Highway Ends.” He grew up in Traer and now lives in Cedar Rapids. A version of this column was originally published in the Between Two Rivers newsletter on Substack, betweentworivers.substack.com. It is republished here through the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. Please consider subscribing to the collaborative at iowawriters.substack.com and the authors’ blogs to support their work.