The story of Iowaville

Artifacts, map shed light on life of Ioway tribe

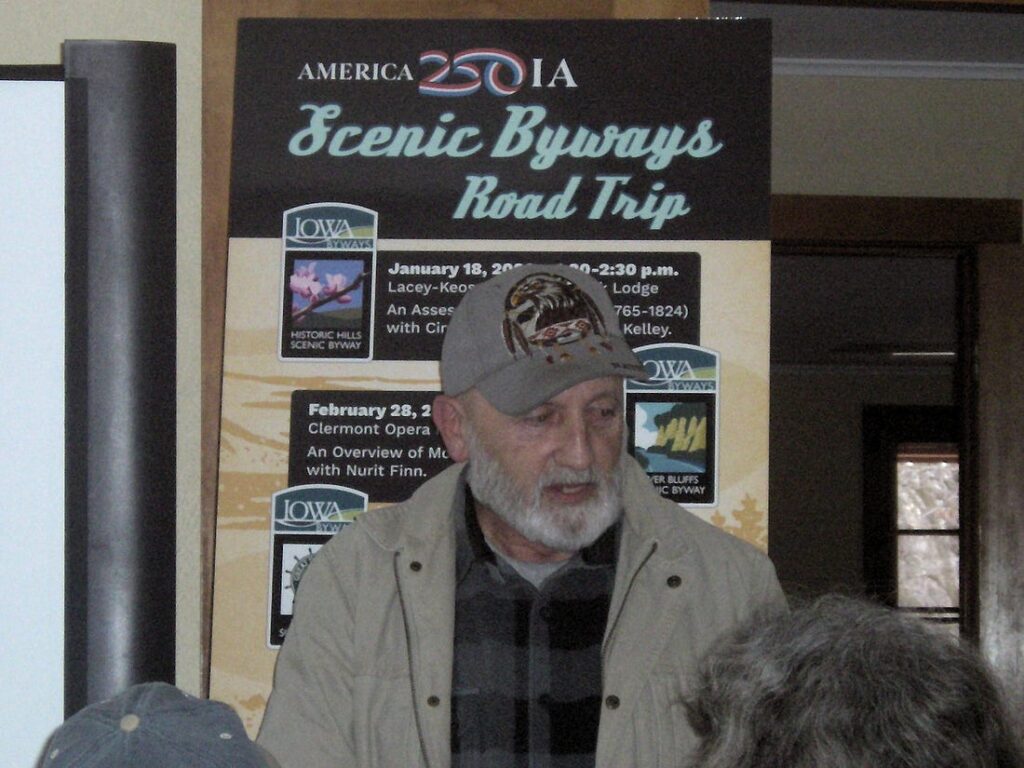

Alan Kelley, tribal historic preservation officer for the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, speaks during the presentation “An Assessment of Iowaville (1765-1824)” Sunday, January 18, 2026, at Lacey-Keosauqua State Park near Keosauqua, Iowa. PHOTO BY JEFF MORRISON

KEOSAUQUA — A celebration of America’s history started with a story of the tribe that gave the state of Iowa its name.

“An Assessment of Iowaville (1765-1824)” at Lacey-Keosauqua State Park Lodge on Sunday, Jan. 18, was the first in a series of statewide presentations connected to the United States’ 250th anniversary. It’s being put on by the Iowa Department of Transportation in conjunction with Iowa Scenic Byways.

Alan Kelley, tribal historic preservation officer for the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, and Cindy Peterson, research director with the University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist, were the speakers for this event.

We don’t know what name the Ioway people gave their large village in the northwest corner of Van Buren County, but white settlers called their own place near the site Iowaville in honor of them. A cemetery by that name exists today and was the burial place of Chief Black Hawk before his remains were stolen.

Kelley began by talking about his interest in archaeology and preservation. He remembered how his grandmother cried about people looting artifacts from tribal land. In addition, “the state of Missouri was telling me that there was never any Indians in Missouri. … In Mound City, they said there was never any mounds there.” He saw a need to keep the tribe’s past alive for the present and future.

The Ioway, or Báxoje, Indians lived in Wisconsin before moving across northern Iowa in the 16th and 17th centuries. The tribe had a large presence in the Council Bluffs area before a smallpox epidemic in 1765. That’s when they moved southeast, to southern Iowa, and set up a village along the Des Moines River.

We know about their movements from a map drawn in 1837 by an Ioway chief whose name translates to No Heart of Fear. No Heart is Kelley’s ancestor and was the brother of Chief Mahaska, namesake of that county. No Heart drew the map to persuade the U.S. government “why they should be fairly compensated for the sale of their ancestral homeland,” said Peterson. Although the map doesn’t visually correspond to the geography used on maps today, it shows major rivers and their branches to great effect. This year, a new book, This Is the Route of My Forefathers, uses the map as a basis to provide a history of the Ioway.

“We weren’t a big threat to anyone,” Kelley said of the Ioway. “We actually surrendered to the state of Iowa, you know, just so we could stay in Iowa. And they said if we surrendered, that we could stay in the state of Iowa.”

But by 1837, other tribes were dominant in Iowa and they became the main parties to treaties and land cessions. The Ioway were pushed south and west and eventually assigned to a reservation at the very southeast corner of Nebraska/northeast corner of Kansas. Some Ioway later moved to Oklahoma.

Iowaville disappeared.

In 1970, a farmer doing deep plowing for the first time turned up so much material he called a professor at Parsons College in Fairfield. Dean Straffan immediately knew it was an Ioway settlement because of the age of the artifacts and general location, Peterson said. For two summers, he and students collected items on the ground (no digging) and found flints, tiny pieces of kettles, and lots of pipes made with red pipestone. This pipestone, originally from what’s now Pipestone National Monument in Minnesota, was sacred “because it was red, it was the blood of the Indians,” Kelley said.

“We knew where the site was, so why on earth did we need to do archaeology then in 2010?” Peterson said. After the 1970 discovery, “a lot of artifact collectors said, ‘Oh wow, this is amazing. Let’s go out here and collect all the time without permission.’ Most of them [did it] without permission from the landowner or the tenant farmer.” Thousands of artifacts disappeared into private collections.

In 2010, thanks to a $25,000 grant from the State Historical Society of Iowa, plus matching funds, nearly 100 volunteers spent four weeks methodically checking the site. Steven DeVore from the National Park Service did geophysical surveys that revealed where the magnetic signature had changed, indicating that deeper soil had been disturbed. That survey told them where to dig.

“If you don’t count the plant remains, like burned seeds and burned wood, and you don’t count the animal bone remains, we found about 5,000 artifacts,” Peterson said. They found copper kettles and kettle scrap, chip stone tools, and on the last day at the last site, a storage pit with gun barrels, knives, and a perforated bear-tooth necklace.

Given how everything was picked over after 1970, and the official dig in 2010, is there anything left at the site? “Holy cow yes,” Peterson said. “It all can tell us such an amazing story about this tribe this place is named after. There are so many features left here. This isn’t only just a National Register site, this is eligible to be a National Historic Landmark.”

There’s just one catch: The owner of the land refused to sell, and told his children before he died never to sell it either.

Jeff Morrison is the writer behind the website “Iowa Highway Ends.” He grew up in Traer and now lives in Cedar Rapids. A version of this column was originally published in the Between Two Rivers newsletter on Substack, betweentworivers.substack.com. It is republished here through the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. Please consider subscribing to the collaborative at iowawriters.substack.com and the authors’ blogs to support their work.